Anyone who knows me will know that I have a great interest in literature generally, and in Japanese literature in particular. I write my own stories, essays and so on, but I am also interested in translating Japanese literature and introducing it to a Western audience. For instance, at the moment, when I have time, which is not often, I am trying to translate Nagai Kafu’s Dwarf Bamboo into English. I have written to a number of professors whom I know to be interested in Kafu or in Japanese literature, to ask for advice in the best way to bring my translation to a public audience, but most of the time I have not even had replies. It seems these professors have better things to do than worry about the promotion of Japanese literature. I even discovered an association dedicated to translated Japanese literature in English, and wrote to them explaining I had studied Japanese literature at Kyoto University and so on, and that I’d love to assist in introducing it to a Western audience. I got no reply.

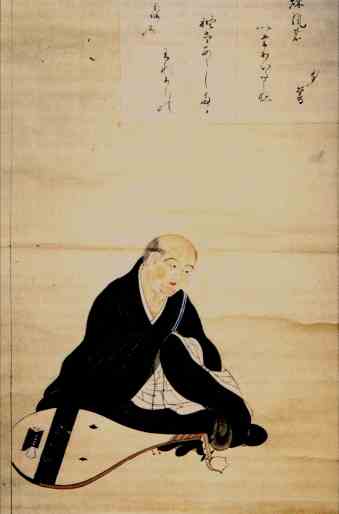

I don’t know exactly what’s going on here, but I am left with the taste of snobbery and clique-ism in my mouth from such encounters, or non-encounters. Probably I need the right introductions and so on. To me this kind of academic clique-ism is not what literature is about. In fact, it is the very opposite of what literature is about. So, I continue in my own way. Here I would like to present the opening section from a work of classical Japanese literature. The work is called Houjouki, or A Record of my Hut. I don’t have all the information at my fingertips right now, but I believe it was written in the twelfth century. It is a discursive work by a character called Kamo no Choumei, who ended his days as a hermit living in a kind of portable hut of his own devising. The work details certain experiences that Choumei had which led him to the – very Buddhist – realisation that all things pass. These experiences were a series of catastrophes which struck the capital of the day. Of course, I feel that such a work might be appropriate for our own times, when the world as we have known it since the industrial revolution is on the point of collapse.

I don’t suppose that Choumei gave a hoot about things such as copyright, but of course, the work is long out of copyright by now, if it was ever in copyright. I present it here freely in my own translation – which I may try to improve on if I get a moment here and there – in the free spirit that literature should be created and disseminated, and a pox on petty professors and publishers (This doesn’t mean I don’t have to try and make a living with my own works, I might add. Heigh ho!):

The current of the river flows unceasing, and the water, ever-changing, is not that which flowed here first. In the backwaters, bubbles wink out and bubbles appear, but never have they been known to remain for long. And thus too the people of this world and the places in which they dwell.

In the resplendent capital, the dwellings of the mighty and the low line up their roof-ridges, their tiles vying for height. It seems that they have spanned the generations, that they stand eternal, but enquire and you will find the houses that stood of old are all too rare. Perhaps they burned down last year, and in their place, another building. Perhaps what was a great house has crumbled away, and now a small house stands there. And those that dwell within the buildings are also thus. The place is the same, and the people here are many, but of the people I knew of old perhaps only one or two remain in twenty or thirty. This morning someone dies, this evening someone is born. Thus are human lives nothing more than bubbles in a stream.