This week, I received a parcel from Japan. It had been sent by someone at whose house I was frequently a guest when I lived in that country. There was a small slip of a note accompanying the gift inside. The note contained nothing of a personal nature, so I feel no qualms in translating it – into rather awkward English – here:

"I have long neglected to write; does your life continue as normal? The leaves of the trees are turning yellow and crimson, and Japan’s autumn is deepening.

"The other day, in Tokyo, I came upon this 'karigane' tea from Uji – please try it. If it is good, I shall send some more."

What I liked about Japan seems distilled into small things, and these small things are also my continuing link with that place.

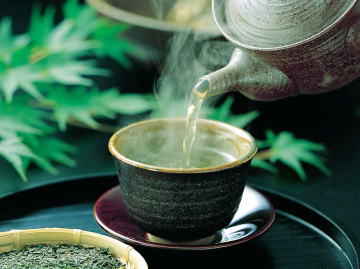

In my room, by the ornamental fireplace, is a 'chakoro' or tea-burner. Inserting a night-light (also, rather appropriately called 'tea-lights') into the tea-burner heats a little earthenware dish that rests on top. When you place tea leaves – green tea leaves – in this dish, they give off a very fresh, pleasant, somehow resinous aroma. When the tea leaves thus roasted are used to brew with, the tea produced has a different, more delicate flavour (it also has less caffeine).

This aroma is one of my links with Japan, and for me contains a whole world of meaning. I believe I first smelt this aroma in Uji, and that is certainly the place with which I associate it. I have lived in Japan twice. The second time, I spent some months in the town of Uji, which lies to the south west of the former capital Kyoto. Uji is famous for two things – it is the setting of many scenes in one of the world's earliest novels, The Tale of Genji, and it is also the home of the finest Japanese tea. It is perhaps little wonder, then, that one of the main influences that Japan has had upon me is to instil in me the habit of drinking green tea.

When I say that I am interested in Japanese tea, people usually ask me if I mean the tea ceremony. The simple answer is 'no'. I have tried the tea ceremony, but I found it rather stiff and artificial. Perhaps this artificiality seems less oppressive if you keep practising it, but I never got that far. Most of what I know about Japanese tea drinking is what I learnt at a little shop called Akamonjaya, on a road filled with the scent of roasting tea, near the temple Byodoin, which appears on the back of the ten yen coin.

The proprietress of this establishment taught me the proper way to prepare green tea, which, apparently, is not the way most Japanese these days prepare it. From her I learnt that quality green tea – gyokuro – should be prepared in a very small pot, called a hohin (which translates as something like "pot of treasure"). The water should only just cover the leaves. That way the leaves can be used again and again. For genmaicha or low quality sencha, you can use a dobin (an ordinary Japanese tea-pot) and put in plenty of water.

Well, I’m hardly an expert, and my knowledge of green tea does not really extend much further than that. For instance, one of the areas in which I am struggling is that of hojicha, the roast tea mentioned above. You can buy it pre-roasted, but Akamonjaya sold special packets of tea for use with the chakoro (tea-burner). The proprietress told me that you can really use any tea in the chakoro, but so far, apart from the special packets I bought at her shop, I have not found any that produce the same aroma or flavour.

It has been over a year since I left Japan, and most of my best tea – the expensive and exquisitely packaged gyokuro and so on I brought back with me – has now gone. I only have half a packet left of the special tea for use with the chakoro. However, I do know that the special tea is a variety of karigane. "Karigane" might be translated literally as "the sound of geese"; a little less literally, I think, as, "the cry of geese". I think it actually refers to tea that is very fresh and has a mixture of leaves and stem, but this, too, is a point I am yet to verify.

Although I am not an expert, because I really got used to Japanese tea in Uji, the tea capital, I have become very fussy. I will try the karigane that has been sent to me in the chakoro. Perhaps it will work. I hope so.

These are the difficulties that face the tea drinker, but such difficulties make the tea so much more precious to me. It is almost Christmas, and lately I am inclined to find gifts that are permanent rather depressing. Gifts, such as tea, that are used up in the making of moments and which disappear – these are the most precious kind.

Such are the gifts that currently form my ties with Japan. Incidentally, the habit of drinking tea, and the very word 'cha' also form ties between England and Japan. Both nations are tea-drinkers, and the Japanese word for tea (cha), has entered into English slang. I rather think the word came to England from its original source, however, which is China. There’s a phrase in English, "I wouldn’t do that for all the tea in China." This rather implies that tea is a heavenly reward.

Q,

The things that are sacred to us, the things we are fussy over, become a kind of ceremony in themselves, don’t they? A religion of the individual, or the Church of Yourself. These are such beautiful things to see in other people. These small things define us, color us in. I try to imagine what your tea-burner smells like, but, having never smelled one before, my brain can only substitute the bright green smell of freshly cut grass, and I am certain this smell is far too wild, too coarse – a vulgarity where grace should be.

Lovely entry.

Peace.

Hello M,

I wish I could accurately describe the smell. It starts off with something of the freshness of pine (though somewhat different), but as it progresses, gets closer and closer to the smell of a pudding, such as apple crumble.

Well, thanks for dropping by. Must get breakfast. Bestest,

Q.

Анонімний writes:All people deserve wealthy life and loans or just financial loan can make it better. Just because people’s freedom depends on money.